Executive Summary

Much like any subject matter these days, there is no shortage of expert advice offered up by the financial industry via traditional and social media sources.

Advice often comes in the way of stock recommendations, thematic investment ideas, and investment strategies provided by people considered to be successful investors. However, you rarely hear about one of the most important factors in investing outcomes – the role of chance or randomness.

It may be disconcerting to hear, especially if you are a planner by nature, but factors outside of your control will most likely have a significant impact on your financial well-being throughout your life.

While we may never be able to completely insulate ourselves from randomness, or even to know exactly how big of a role it plays in our lives, we do believe that steps can be taken to reduce the ability for random events to dictate our financial outcomes.

By using Morgan Housel’s book, “The Psychology of Money” as our foundation, this note will explore some time-tested strategies to reduce the role that chance has on your financial well-being.

The Role of Randomness:

Cromwell’s rule (statistics): Never say something cannot occur, or will definitely occur, unless it is logically true (1+1=2). If something has a one-in-a-billion chance of being true, and you interact with billions of things during your lifetime, you are nearly assured to experience some astounding surprises, and should always leave open the possibility of the unthinkable coming true.1Source: Morgan Housel https://collabfund.com/blog/little-ways-the-world-works/ 2Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cromwell%27s_rule

Everyone knows the story of Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft who became one of the richest people on the planet. It is a great success story, the undeniably brilliant and hard-working Gates dropping out of Harvard to launch a company with his friend Paul Allen that goes on to be one of the most valuable and influential firms in the world. However, Morgan Housel tells a lesser-known Bill Gates story in The Psychology of Money illustrating just how important the role of luck was in his success.

Gates was born in 1955 in Seattle and attended Lakeside Prep High School, where he met Paul Allen. Bill and Paul were incredibly fortunate to be attending Lakeside, as it was one of the few schools in the entire country to have a computer in the 1960s and they were both fascinated with it. “Most university graduate schools did not have a computer anywhere near as advanced as Bill Gates had access to in eighth grade,” Housel writes. By the time he and Paul launched Microsoft in the mid-70s, they had over a decade of experience working with computers. In this example, we see Bill Gates become one of the richest people on the planet, in part, because he was one of the lucky few students in the country to have early access to a technology that would come to dominate the world. “If there had been no Lakeside, there would have been no Microsoft,” Gates once told Lakeside’s graduating class.3Source: Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money

Housel contrasts this story of good fortune with a related story that illustrates the flipside of luck, the story of Kent Evans. Kent grew up with Bill Gates and Paul Allen and he and Bill became best friends. Bill considered him the smartest kid in class and like the other two, he was fascinated by computers. Even more so than Paul, Kent shared Bill’s focus and career ambition. “We would have kept working together. I’m sure we would have gone to college together,” Bill once said. It is conceivable that Kent would have gone on to be another founder of Microsoft. Unfortunately, Kent’s story was cut short by a tragic mountaineering accident that cost him his life before he graduated high school. Housel summarizes, “For every Bill Gates there is a Kent Evans who was just as skilled and driven but ended up on the other side of life roulette.”

People are pattern-seeking creatures, and as such, we have a desire to ascribe a reason for things occurring. In short, we need a story, whether true or not, that helps align events with our meta-story of how the world works for things to seem less chaotic (see Calvin’s snow angel narrative at right). However, completely random events happen all around us every single day. Many of these events are small and inconsequential but others are global and impact nearly everyone. Rather than attempting to retrofit convenient stories around these events, acknowledging and planning for randomness in the world may yield better results.

Take the Covid-19 pandemic, for example. A novel virus sprang onto the world stage in early 2020, ultimately killing millions, and essentially shutting down large parts of the global economy. Many previously successful small business owners, especially those whose businesses relied on foot traffic, faced difficult times and many companies didn’t survive. However, if you happened to be working for a large US tech company during the pandemic, you may very well have made a fortune as business boomed and company stock skyrocketed.

The pandemic created a “best of times” financial situation for some, and the “worst of times” outcome for others. It is easy to assume that people that end up rich and successful must be smarter and harder working than others. However, outcomes themselves often say very little about the career and investment decisions that led up to them, and far more about the power of randomness and chance in the world. Replace the pandemic in the example above with a widespread global hacking event that upended technology companies and the outcomes may have been reversed.

One of the lessons that can be drawn from The Psychology of Money is that luck, both good and bad, can play a significant role in many areas of your life, including in shaping your financial well-being. Much like playing poker, you cannot control the cards that you’re dealt, you can only play the hand. Let’s explore some additional lessons from the book so that we can learn to play our hands well.

Defining “Enough”:

“At a party given by a billionaire on Shelter Island, Kurt Vonnegut informs his pal, Joseph Heller, that their host, a hedge fund manager, had made more money in a single day than Heller had earned from his wildly popular novel Catch-22 over its whole history. Heller responds, “Yes, but I have something he will never have…enough.”

Enough. I was stunned by the simple eloquence of that word – stunned for two reasons: first, because I have been given so much in my own life and, second, because Joseph Heller couldn’t have been more accurate. For a critical element of our society, including many of the wealthiest and most powerful among us, there seems to be no limit today on what enough entails.”4Source: Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money

This story was told by John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, himself a ridiculously wealthy man. The lesson here is simple, wealth is the accumulation of earnings less spending over time. For Joseph Heller, the earnings from his novels over time supported his relatively modest (at least compared to the hedge fund manager) needs. He had his “enough”.

One of the troubling parts of the proliferation of social media over the past decade is that there is no longer any ceiling to social comparisons. You are no longer comparing yourself to just your immediate community, you are comparing yourself to the global community. As a result, if trying to keep up with the Joneses led people to make imprudent financial decisions decades ago, what happens when we compare ourselves to Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk these days? I mean, can you even call yourself rich and successful if you don’t have your own space program (see Bezos doing his best Maverick impression at right)?

Housel begins the book with an example worth mentioning – Ronald Read. Mr. Read was born in Vermont, graduated from high school, got married, and bought a small house at 38. He worked for 25 years fixing cars at a gas station and swept floors as a janitor for 17 years. According to friends, his favorite hobby was chopping wood.

You may be thinking that it is odd that Mr. Read is being mentioned in this note, as his life doesn’t sound particularly interesting. And it wasn’t, he led a quiet and modest life until his death at age 92. It was at that point that the humble janitor made headlines, as news of his more than $8 million estate spread. He left about $2 million to his step kids and the rest to his local library. People wondered if he had hit the lottery or inherited a large sum. He hadn’t, he simply lived a frugal life and invested excess earnings in blue chip stocks. He realized his rather modest “enough” and saved the rest.

The lesson here isn’t necessarily to imitate Ronald Read or Joseph Heller. The lesson is that wealth is less about how much you make and achieving outsized investment returns and more about your savings rate. Wealth is relative to what you need, so we can increase our wealth by needing less and saving more. As Housel summarizes, “Less ego, more wealth.”

The Benefit of Diversification:

“I’ve been banging away at this thing for 30 years. I think the simple math is, some projects work and some don’t. There’s no reason to belabor either one. Just get on to the next.” – Brad Pitt, accepting the Screen Actors Guild Award

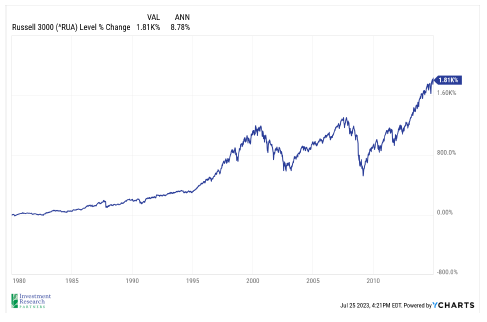

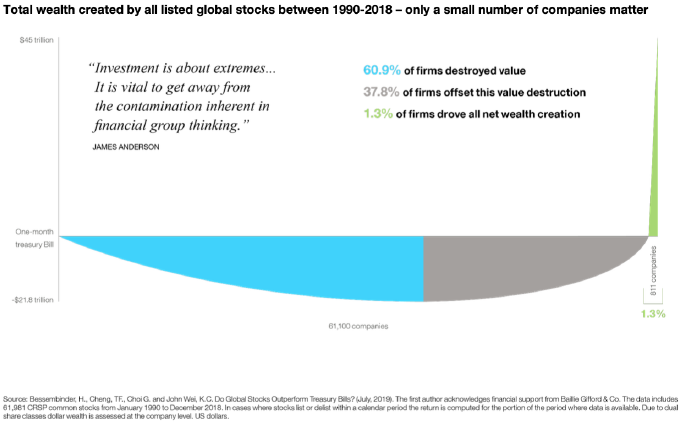

Drawing from research published by JP Morgan Asset Management, Housel shares that from 1980 to 2014, the Russell 3000 index, a broad U.S. stock index, performed well, up nearly 9 percent per year.5Source: JP Morgan’s The Agony & The Ecstasy – Eye On The Market (2014) However, when you dig deeper into the attribution you find that the performance was driven by a very small fraction of its components. According to the study, nearly 40% of all Russell 3000 companies lost at least 70 percent of their value during the period and never recovered. However, a small percentage were home runs that produced staggering returns. “Effectively all of the index’s overall returns came from 7% of component companies that outperformed by at least two standard deviations.”

The image at right, from investment firm Baillie Gifford, illustrates a similar conclusion drawn from a study on global stocks. Again, a small percentage of wildly successful investments drove net wealth creation. Housel provides additional examples of a handful of successful investments in both venture capital and art investing more than making up for otherwise mediocre investment returns.

It is difficult, even for investment professionals, to consistently know which companies will turn out to be the biggest winners. As a result, it makes sense to have a diversified portfolio in an effort to capture those outsized winners. To paraphrase Pitt’s quote from earlier, if one path to making great movies is simply to make a lot of movies, one path to investment success is to make a lot of investments.

And Finally, Patience:

“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it; he who doesn’t, pays it.” attributed to Albert Einstein

The human brain is built for linear, not exponential thinking, which is why even the most intelligent of us often underestimate the power of small things over very long time periods. Housel tells the story of computing storage beginning in the 1950s exploding to become 30 million times larger today, something that would’ve been inconceivable for even the most optimistic computer expert back in the 50s.

The investing story Housel tells to illustrate the importance of exponential thinking is a story about the most famous investor in the world – Warren Buffett. He points out that there are more than 2,000 books dedicated to Buffett and nearly everyone knows about his investment success while at Berkshire Hathaway. However, those books often overlook Buffett’s secret to success. Consider the following:

• Buffett began serious investing at age 10

• He became a millionaire at age 30

• His wealth at the time The Psychology of Money was published in 2020 was $84.5 billion

• Of that, $84.2 billion of that was earned after age 50 (he was age 90 in 2020)

• And $81.5 billion was earned after he qualified for Social Security in his mid-60s

That means that over 99 percent of his wealth came after his 50th birthday and over 96 percent after he qualified for Social Security. Warren Buffett is undoubtedly a brilliant investor. However, we most likely wouldn’t have heard of him if he started investing at 30 and retired at 65. Buffett’s superpower from an investing standpoint is longevity. He started investing as a child and has continued to do so for more than three-quarters of a century since that time.

Longevity and patience play such an important role in investing success, that Housel summarizes that chapter of the book with the following passage:

“There are books on economic cycles, trading strategies, and sector bets. But the most powerful and important book should be called ‘Shut Up And Wait’. It’s just one page with a long-term chart of economic growth.”

Summary:

Morgan Housel’s book, The Psychology of Money is full of interesting stories and sound advice, and reading it in full is well worth your time. He makes a compelling case for the outsized impact that luck can have on our lives but follows that with equally important factors that are well within our control. The distilled lessons focused on in this note: living within means, diversifying your assets, and exercising patience, will mean something different to everyone who reads this piece. However, we believe that integrating these lessons into financial decision-making can help lead to better financial outcomes regardless of your financial situation.

References

- 1Source: Morgan Housel https://collabfund.com/blog/little-ways-the-world-works/

- 2

- 3Source: Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money

- 4Source: Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money

- 5Source: JP Morgan’s The Agony & The Ecstasy – Eye On The Market (2014)